Review of Juliet Barnes (2013), The Ghosts of Happy Valley: Searching for the Lost World of Africa’s Infamous Aristocrats. London: Aurum.

In The Ghosts of Happy Valley (hereafter, Ghosts), Juliet Barnes gives an account of her investigations into the lives and deaths of a small group of white Europeans who settled in Wanjohi Valley (or ‘Happy Valley’) in the 1920s and 1930s. To give you an idea of the tone and its intended audience: Ghosts book was reviewed positively in The Spectator (but you'll have to take my word for it - it’s behind a paywall).

Juliet Barnes is a white Kenyan citizen, the granddaughter of settlers who were farmers near Mount Kenya. Despite her ethnic, historical, cultural, and educational ties to Britain, Barnes considers Kenya her home while tacitly acknowledging the complications that such an attachment entails. In the very first paragraph of the book, Barnes describes a party at her mother’s house in Kenya where Solomon Gitau was the only black guest in a sea of white women. He is described thus:

'I looked curiously at this dark, tall man with his white teeth, black piercing eyes, and slightly unkempt appearance. … His surname, Gitau, is a Kikuyu name, but Solomon bears little resemblance to these characteristically short, light-skinned African people.' (p.3)

This description remains mired in colonial stereotypes and the hierarchical categorisation of African ethnic groups according to the value placed on phenotypes closest to the white European ideal. [2] This passage and its perpetuation of a racist conceptual scheme is symptomatic of the attitude towards race/racism throughout Ghosts. Occasionally Barnes makes racism her focus, but she fails to develop this into a critical perspective on the processes and effects of settler colonialism in Kenya. For instance, the recruitment of Black African men into servitude by the memsahibs of Happy Valley in the 1920s is described with apparent awareness of the damage caused by such a racialised hierarchy (pp.30-31), but later in the book, that fact that Barnes herself employs a Black Kenyan woman called Alice as a maid (‘my house help’) is not viewed critically, despite the obvious continuity between the two situations (p.248).

Frustratingly, Barnes demonstrates an implicit awareness of the intersection of race and gender as far as her own experience goes: ‘a white woman…my skin colour and my sex rendering me doubly harmless’ (p.148). She thus acknowledges the function of white privilege in contemporary Kenya while ignoring the mechanisms that maintain it, refusing to reflect on the elements of Kenya’s colonial past that harm(ed) Africans. This is especially difficult to digest given the plentiful sympathy that Barnes expresses for the white settlers; for example those who were forced to leave Kenya against their wishes (e.g. pp.224-225). This lack of attention to the effects of racism in postcolonial Kenya is a serious omission, not least because it precludes any reflexive consideration of her positionality as the author. This is particularly critical given that it is in part Barnes’ ability to draw parallels between the settlers she researches and her own family's experiences that underwrites her authority on the topic.

Barnes’ writing echoes dominant representations of European colonisation of Africa. In the historical narrative offered in Ghosts, the white settlers arrived in an otherwise ‘uninhabited’ Wanjohi Valley. Barnes’ descriptions of beautiful plants and once-lush gardens are a synecdoche of European imperialism: a natural world untouched by human hands, being harnessed and cultivated for the first time. The application of this colonial logic allows her to posit that for white people to claim a foreign land in this way was at worst morally negligible. In an intriguing parallel, Barnes describes the Gĩkũyũ harvesting trees for firewood, changing the landscape of Wanjohi Valley in a comparable way to the colonisers did. It comes as little surprise that Barnes and her white interlocutors consider this irresponsible and damaging. This is a distinctive expression of what Patricia Lorcin names ‘colonial nostalgia’, which suffuses white women’s writing about their experiences in colonised eastern Africa. This is the nostalgia for a romantic idea of ‘vanishing Africa’ of formerly ‘empty’ land and pristine scenery, that they felt would soon be completely effaced by modernity in the hands of Africans released from the ‘guidance’ of colonial control. [3]

Among Barnes’ stated motives for writing Ghosts is to record and celebrate Solomon Gitau’s heroic conservation efforts; indeed, the book is dedicated to him. However, the singularity of Gitau’s environmentalist mission is overemphasised to the point that he appears to be the only Kenyan who cares whatsoever about environmental issues (with the exception of a fleeting mention of Wangari Maathai, p.141). It is obviously true that many people living in rural and urban areas have done, and are doing, environmentally damaging things; this is true all over the world, not only in Kenya. Reading Ghosts, the impression is given that a concern for the environment is basically a white trait, a hobby shared by an enlightened minority. The lack of critical reflection on the complexity of the structures in which Kenyans find themselves impoverished belies Barnes’ praise for Gitau. Combined with her reaction to his appearance, quoted above, the message seems to be that Gitau isn’t like other Gĩkũyũ people: he’s better.

Ghosts is an illustration of the significance of what white people do with our memories and histories of colonisation. The politics of representing ‘Africa’ is articulated particularly sharply by the Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina in his well-known satirical article ‘How to Write about Africa’. [4] Wainaina enumerated the litany of clichés that serve as shorthand for descriptions and observations about ‘Africa’, many of which Barnes ends up employing. As long as whites continue to benefit from coloniality and colonisation, which we do, then if we write postcolonial history we must incorporate a critical analysis of racism, colonial power relations, and our own positionality and complicity with these. Otherwise we will risk repeating the tropes of colonial nostalgia.

NOTES

[1] Whereas Barnes uses the spelling ‘Kikuyu’, I follow the example of Wairimũ Njambi, and other Gĩkũyũ scholars, in their spelling of Gĩkũyũ.

[2] Carolyn M. Shaw (1995), Colonial Inscriptions: Race, Sex, and Class in Kenya, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp.185-203.

[3] Patricia M. E. Lorcin (2012), Historicizing Colonial Nostalgia: European Women's Narratives of Algeria and Kenya 1900-Present, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p.159.

[4] Binyavanga Wainaina (2005), ‘How to Write about Africa’, Granta 92. Accessible via: http://www.granta.com/Archive/92/How-to-Write-about-Africa/Page-1

In The Ghosts of Happy Valley (hereafter, Ghosts), Juliet Barnes gives an account of her investigations into the lives and deaths of a small group of white Europeans who settled in Wanjohi Valley (or ‘Happy Valley’) in the 1920s and 1930s. To give you an idea of the tone and its intended audience: Ghosts book was reviewed positively in The Spectator (but you'll have to take my word for it - it’s behind a paywall).

|

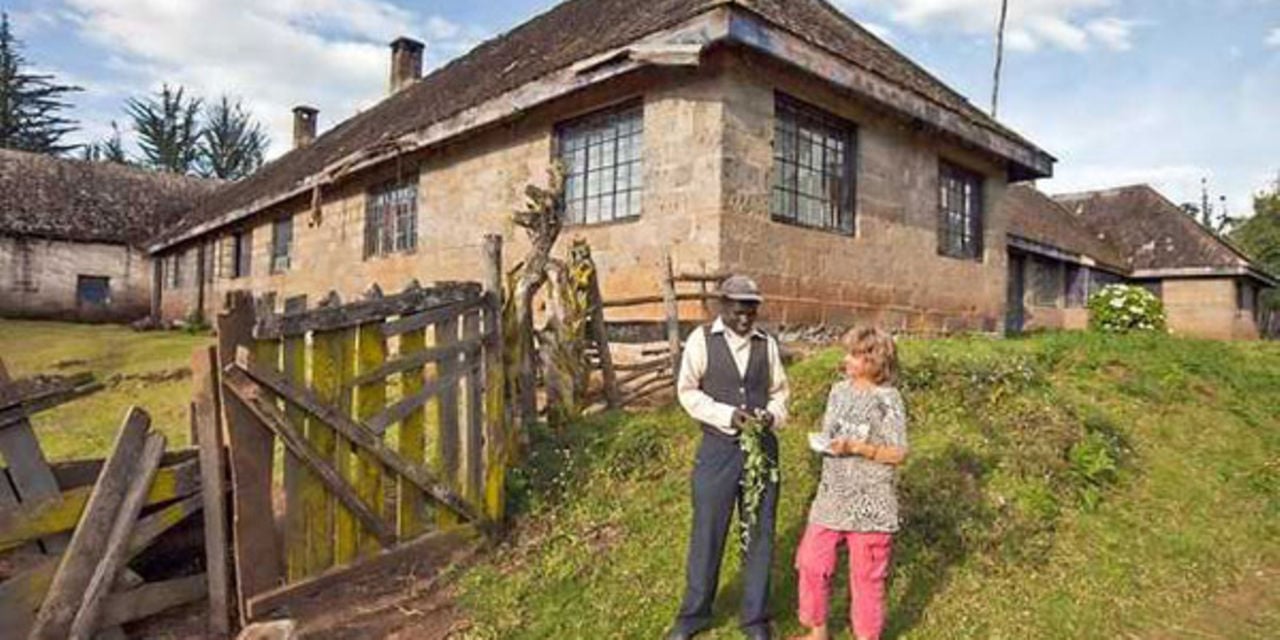

| Solomon Gitau (l) and Juliet Barnes (r) at Clouds House in Nyandarua. Photo (c) Eliud Maumo 2019 |

It is clear from the sheer number of books about Happy Valley, that there remains a great deal of public interest in the salacious and exaggerated stories of this historical neighbourhood. With her friend Solomon Gitau by her side, Barnes travelled throughout Wanjohi Valley over a period of many years, tracking down and visiting the former homes of (in)famous European settlers, many of them ruins and some of them lived in now by local Gĩkũyũ people. [1] In Ghosts, Barnes traces her progress over many years of research, sporadically enriching her account with details of the country’s colonial past and her place within it. Barnes is concerned above all with the intimate and domestic details of the lives, homes, and gardens built in the region by the aristocratic and upper-class Happy Valley settlers. Through rediscovering the now decrepit houses in which their many dramas unfolded, Barnes aims to find answers to some of the questions that linger like the ghosts of her title. What physical trace remains of the lives, projects, and passions of these exceptional people? While her investigations offer some interesting insights into the ‘lost world’ of the title, my reading suggests that Barnes’ narrative (maybe Barnes herself) is haunted by ghosts of a different nature: critical questions of the politics of representation, and of colonial memory, which remain absent and unanswered.

Juliet Barnes is a white Kenyan citizen, the granddaughter of settlers who were farmers near Mount Kenya. Despite her ethnic, historical, cultural, and educational ties to Britain, Barnes considers Kenya her home while tacitly acknowledging the complications that such an attachment entails. In the very first paragraph of the book, Barnes describes a party at her mother’s house in Kenya where Solomon Gitau was the only black guest in a sea of white women. He is described thus:

'I looked curiously at this dark, tall man with his white teeth, black piercing eyes, and slightly unkempt appearance. … His surname, Gitau, is a Kikuyu name, but Solomon bears little resemblance to these characteristically short, light-skinned African people.' (p.3)

This description remains mired in colonial stereotypes and the hierarchical categorisation of African ethnic groups according to the value placed on phenotypes closest to the white European ideal. [2] This passage and its perpetuation of a racist conceptual scheme is symptomatic of the attitude towards race/racism throughout Ghosts. Occasionally Barnes makes racism her focus, but she fails to develop this into a critical perspective on the processes and effects of settler colonialism in Kenya. For instance, the recruitment of Black African men into servitude by the memsahibs of Happy Valley in the 1920s is described with apparent awareness of the damage caused by such a racialised hierarchy (pp.30-31), but later in the book, that fact that Barnes herself employs a Black Kenyan woman called Alice as a maid (‘my house help’) is not viewed critically, despite the obvious continuity between the two situations (p.248).

Frustratingly, Barnes demonstrates an implicit awareness of the intersection of race and gender as far as her own experience goes: ‘a white woman…my skin colour and my sex rendering me doubly harmless’ (p.148). She thus acknowledges the function of white privilege in contemporary Kenya while ignoring the mechanisms that maintain it, refusing to reflect on the elements of Kenya’s colonial past that harm(ed) Africans. This is especially difficult to digest given the plentiful sympathy that Barnes expresses for the white settlers; for example those who were forced to leave Kenya against their wishes (e.g. pp.224-225). This lack of attention to the effects of racism in postcolonial Kenya is a serious omission, not least because it precludes any reflexive consideration of her positionality as the author. This is particularly critical given that it is in part Barnes’ ability to draw parallels between the settlers she researches and her own family's experiences that underwrites her authority on the topic.

Barnes’ writing echoes dominant representations of European colonisation of Africa. In the historical narrative offered in Ghosts, the white settlers arrived in an otherwise ‘uninhabited’ Wanjohi Valley. Barnes’ descriptions of beautiful plants and once-lush gardens are a synecdoche of European imperialism: a natural world untouched by human hands, being harnessed and cultivated for the first time. The application of this colonial logic allows her to posit that for white people to claim a foreign land in this way was at worst morally negligible. In an intriguing parallel, Barnes describes the Gĩkũyũ harvesting trees for firewood, changing the landscape of Wanjohi Valley in a comparable way to the colonisers did. It comes as little surprise that Barnes and her white interlocutors consider this irresponsible and damaging. This is a distinctive expression of what Patricia Lorcin names ‘colonial nostalgia’, which suffuses white women’s writing about their experiences in colonised eastern Africa. This is the nostalgia for a romantic idea of ‘vanishing Africa’ of formerly ‘empty’ land and pristine scenery, that they felt would soon be completely effaced by modernity in the hands of Africans released from the ‘guidance’ of colonial control. [3]

|

| Buxton House, main picture, and Ghosts, inset. Photo (c) John Fox 2014 |

Among Barnes’ stated motives for writing Ghosts is to record and celebrate Solomon Gitau’s heroic conservation efforts; indeed, the book is dedicated to him. However, the singularity of Gitau’s environmentalist mission is overemphasised to the point that he appears to be the only Kenyan who cares whatsoever about environmental issues (with the exception of a fleeting mention of Wangari Maathai, p.141). It is obviously true that many people living in rural and urban areas have done, and are doing, environmentally damaging things; this is true all over the world, not only in Kenya. Reading Ghosts, the impression is given that a concern for the environment is basically a white trait, a hobby shared by an enlightened minority. The lack of critical reflection on the complexity of the structures in which Kenyans find themselves impoverished belies Barnes’ praise for Gitau. Combined with her reaction to his appearance, quoted above, the message seems to be that Gitau isn’t like other Gĩkũyũ people: he’s better.

Ghosts is an illustration of the significance of what white people do with our memories and histories of colonisation. The politics of representing ‘Africa’ is articulated particularly sharply by the Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina in his well-known satirical article ‘How to Write about Africa’. [4] Wainaina enumerated the litany of clichés that serve as shorthand for descriptions and observations about ‘Africa’, many of which Barnes ends up employing. As long as whites continue to benefit from coloniality and colonisation, which we do, then if we write postcolonial history we must incorporate a critical analysis of racism, colonial power relations, and our own positionality and complicity with these. Otherwise we will risk repeating the tropes of colonial nostalgia.

NOTES

[1] Whereas Barnes uses the spelling ‘Kikuyu’, I follow the example of Wairimũ Njambi, and other Gĩkũyũ scholars, in their spelling of Gĩkũyũ.

[2] Carolyn M. Shaw (1995), Colonial Inscriptions: Race, Sex, and Class in Kenya, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp.185-203.

[3] Patricia M. E. Lorcin (2012), Historicizing Colonial Nostalgia: European Women's Narratives of Algeria and Kenya 1900-Present, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p.159.

[4] Binyavanga Wainaina (2005), ‘How to Write about Africa’, Granta 92. Accessible via: http://www.granta.com/Archive/92/How-to-Write-about-Africa/Page-1

Comments

Post a Comment